Environmental and Cultural Collapse of Louisiana’s Vanishing Coast

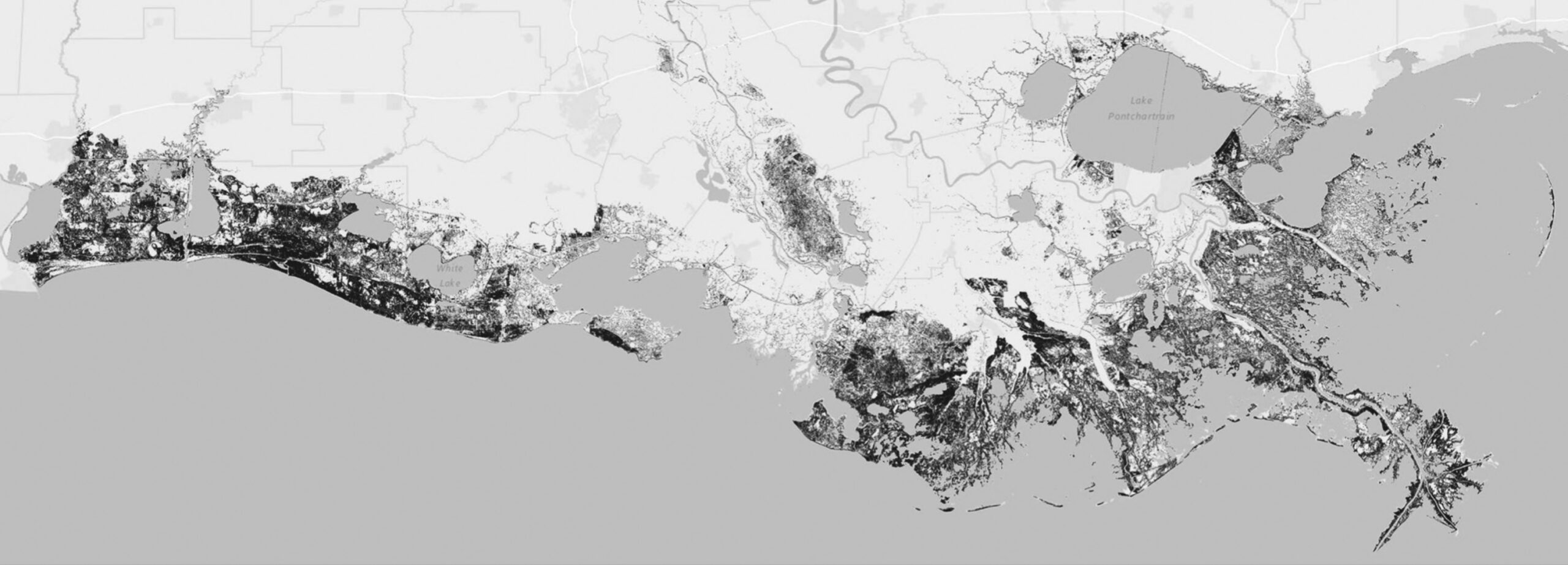

Water levels are rising in Barataria and Terrebonne Bays as Louisiana’s coastline unravels, impacted by environmental changes and industrial pressures.

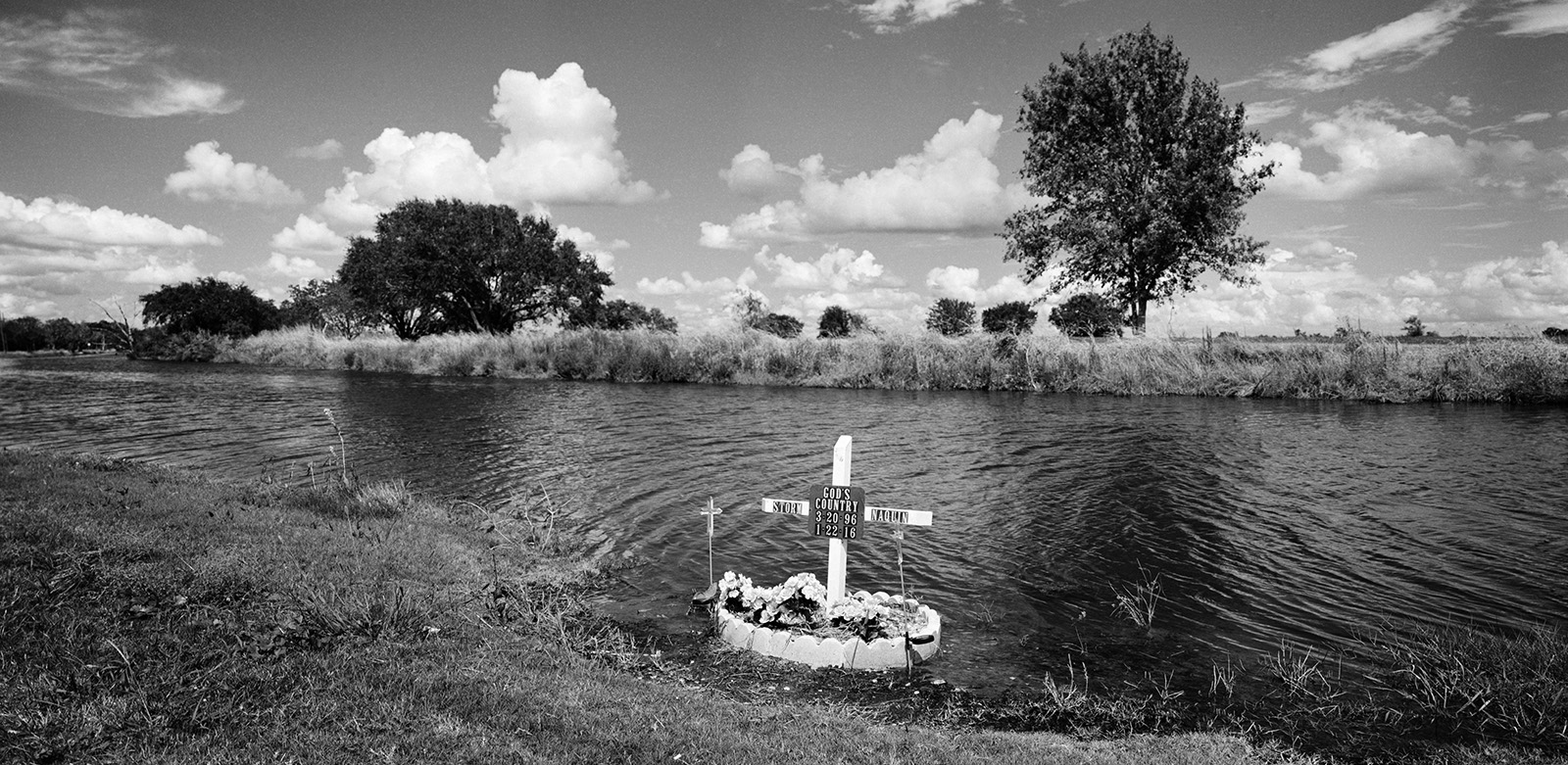

For years, every northward breeze has pushed more Gulf water inland—over marshes, bayou banks, roads, and into people’s homes. In many of these communities, submerged roads are the only links to the outside world.

Louisiana stands at the forefront of global sea-level rise, experiencing the highest rate of coastal erosion in the United States. The state loses roughly 100 yards of land every 30 minutes—an area the size of a football field every half-hour. Alongside global sea-level rise, Louisiana has endured a dozen major storms in this century, including Katrina (2005), Rita (2005), and Ida (2021), which drastically reshaped the state’s coastline. 2023 marked the warmest year on record, and rising global temperatures are only one factor contributing to the ongoing subsidence of Louisiana’s coast. Other causes include oil exploration, altered wetland flows, and the destructive impact of invasive species on marshlands.

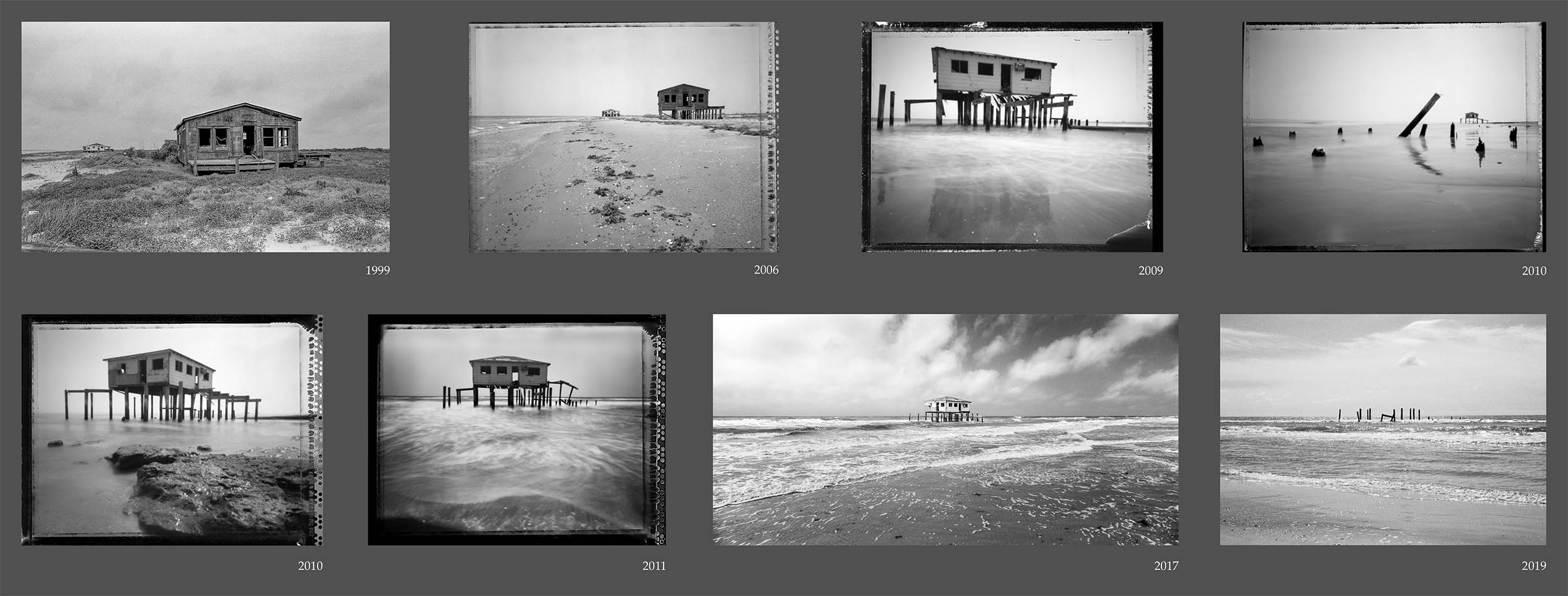

These photographs are results of more than two decades of annual re-visitation of the specific geographic area, The Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary. Witnessing this physical unraveling of landscape became a personal visual metaphor for the disintegration of my native country of Yugoslavia.

Barataria Bay’s barrier islands, some of the youngest and most unstable landforms on earth, are rapidly disappearing due to human intervention in the Mississippi Delta’s natural flow. Timbalier Island, for example, has lost 20 meters per year over the last century.

Coastal disasters, however, are not a recent phenomenon. In the early 1800s, Louisiana’s barrier islands were popular summer resorts for the wealthy families of New Orleans. The Last Island (Isle Dernière) was one such resort, offering steamer lines, cottages, and even a hotel—the John Muggah Ocean House.

In 1856, a powerful Category 4 or 5 hurricane struck Isle Dernière, killing around 200 vacationers and destroying every building on the island. Lafcadio Hearn’s novella Chita: A Memory of Last Island (1889) captures this tragedy.

Several decades later, on October 2, 1893, a Category 4 hurricane hit South Louisiana’s barrier islands at the mouth of Barataria Bay. The community of Chenière Caminada was directly impacted by a 16-foot storm surge, killing over 2,000 people and wiping the village off the map. The Chenière Caminada Hurricane remains one of the deadliest storms in U.S. history. Southern feminist author Kate Chopin referenced the event in The Awakening (1899) and At Chenière Caminada (1894).

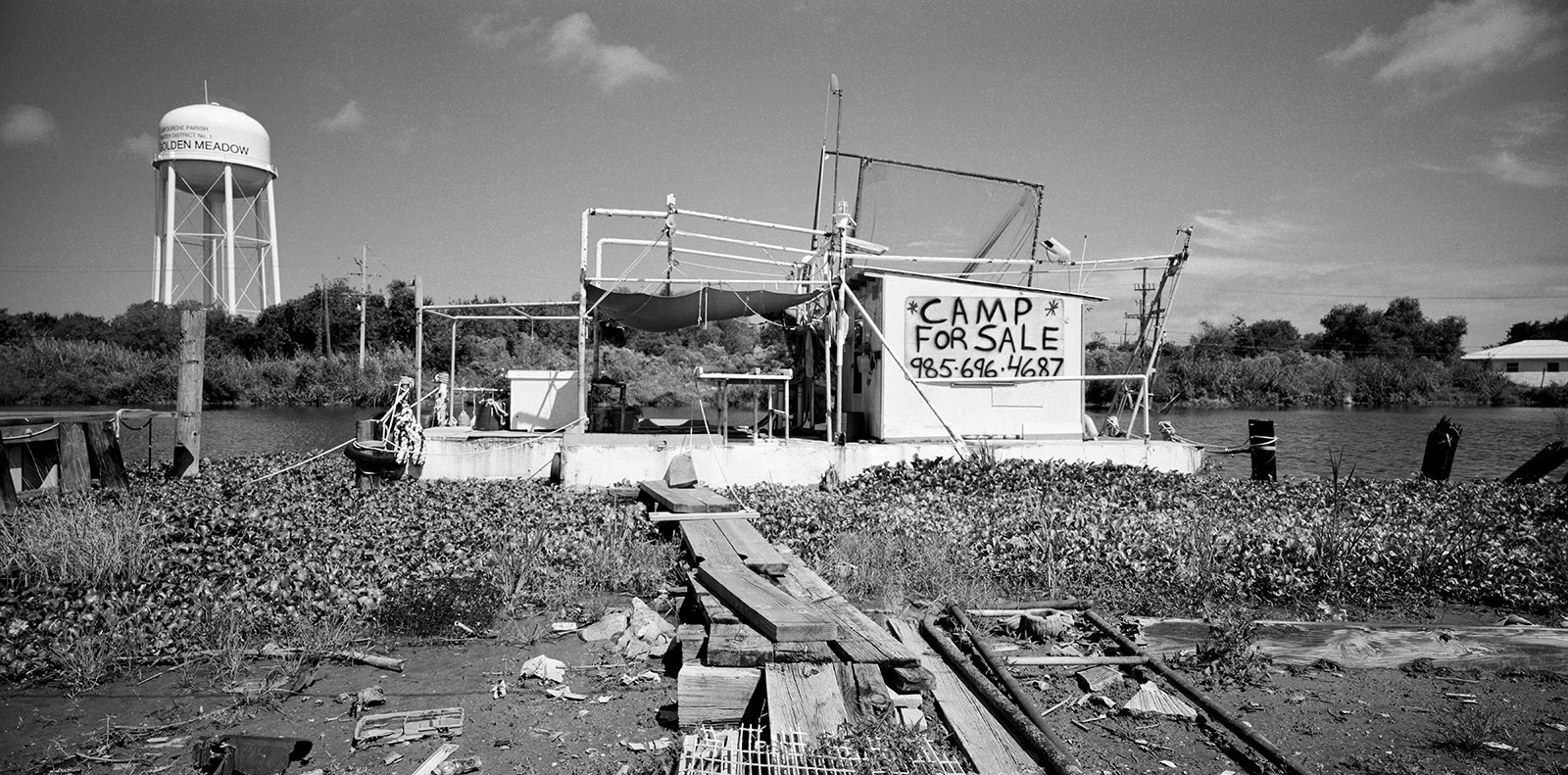

Today, Louisiana’s people and culture are vanishing along with its land.

The people of Louisiana are deeply tied to the landscape they inhabit. Unfortunately, this intimate connection is under immediate threat as the land retreats. Modern technology and engineering can slow coastal erosion but are ineffective at preserving cultural heritage. Indigenous communities, Cajuns, and Asian Americans across South Louisiana are suffering from the loss of natural resources, economic hardship, and direct property damage. Each year, more small communities are abandoned, sinking gradually into the wetlands.

Isle de Jean Charles, home to the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw people, exemplifies this plight. Settled in the 1880s, the community grew from four to 16 families by the 1910 census. Over the past 60 years, the island has lost more than 98% of its land due to rising sea levels, hurricanes, and land subsidence. Once five miles wide, the island is now just a quarter-mile wide. In 2001, the realignment of the Morganza Spillway left the island outside the levee system, exposing it to further flooding and hurricane damage. In 2016, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) awarded the community $48 million to fund its resettlement. After lengthy negotiations, the Tribal Council accepted HUD’s plan, relocating the community to Schriever, Louisiana—40 miles north.

Yet many chose to remain, citing sovereignty, self-determination, and the fight for cultural survival. Tribal members and leaders have not considered the resettlement project a success, and the challenges it poses continue to affect an increasing number of coastal residents.

This is a story of challenges and adaptations. The global environmental concerns that place Louisiana at the center of worldwide attention make this project timely and urgent. It represents the longest undertaking of my career, documenting two decades of relentless landscape shifts and the adaptive responses of communities in our new, warmer, and wetter world.